Key Points

- Owning too many funds has its downsides; owning too few can be bad as well.

- Monte Carlo results can help you determine if you're diversified enough.

- What matters far more than the number of funds you own is the asset class mix of your investments.

How many funds should you own to ensure a successful retirement?

As with so many other questions involving personal finance, there's no single right answer to this question.

The number of funds you should own is going to depend on your investment goals, risk tolerance, and portfolio diversification strategy. Generally speaking, owning a diversified portfolio of mutual funds can help reduce risk and improve returns over the long term.

But--and there's always a but--there are certain types of funds out there that are constructed in such a way that a single mutual fund could be enough.

We'll talk about those kinds of funds in a moment. But a good starting point for most investors is to aim for a diversified portfolio of funds that includes exposure to different asset classes. That asset-class part is key, as we'll soon see. We're talking about the usual suspects here: stocks (and a wide variety of stock types), bonds, and alternative investments such as gold. A commonly cited rule of thumb is to own between 10 and 20 mutual funds, but the actual number will vary depending on your individual circumstances.

Too many funds can lead to unnecessary over-diversification and overlap. There's really no point in owning, say, two index funds that invest in the same index. That's an obvious example, but there are other, less obvious instances where you might have some redundancies. If you own multiple growth stock funds, do you know what the overlap is between the two?

In the end, the number of mutual funds you should own will depend on your individual circumstances and investment goals. But it's mostly not the number of funds that's important. It's what they hold.

Spread It Around

Do you know about life-cycle funds?

A life-cycle fund (also known as a target-date retirement fund) will adjust its holdings over time based on your projected retirement date. So if you're planning to retire 40 years from now, it will be loaded up with stocks. As you approach retirement, it will gradually become more conservative, and take on more fixed-income holdings.

We bring this up because, in this case, a single fund might be all you need. It's a true set-it-and-forget-it investment.

But most investors are going to have at least a few funds. For one thing, you might have certain offerings in your 401(k), but different offerings in your IRA or brokerage accounts. What are the important things to consider in those cases?

We've covered the topic of fees a number of times before. We won't get into that again now (but, in brief: Know what you're paying, and know if there are cheaper alternatives). Second to fees, it's asset classes you want to pay most attention to. We're about to find out why.

When Correlation Does Imply Causation

Consider a couple in their 30s who are hoping to retire at 60. They've read that, at their current age, they should be as aggressive as possible (or as aggressive as they're comfortable being) with their investments if they want to retire that early. This normally means their investments will be more volatile than if they were being more conservative with them.

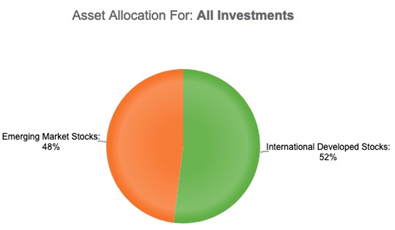

The couple is comfortable with that idea. So they take it to heart, investing everything they have overseas, in emerging markets stocks as well as more developed foreign markets.

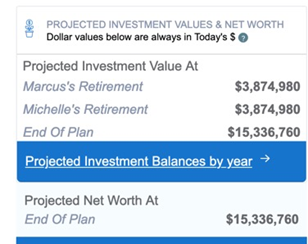

In looking at their plan, at first glance, this seems like a great move. On a straight-line basis, using the WealthTrace Financial & Retirement Planner, we project that they'll have $3.9 million when they retire, and thanks to years of compounding and high investment returns ahead of them, more than $15 million at the end of their lives.

The catch is the 'on a straight-line basis' part. Straight-line returns assume that, year in and year out, the couple's investments return what they're projected to return, with no bear markets or recessions along the way.

That's one way to look at a plan, and although it's not very real-world, it's normally more useful than it might sound for a couple this age. That's because, given enough time, asset class performance should revert to the mean and generate returns that are more or less in line with those straight-line projections, even with bumps and bruises along the way.

The problem in this case, though, isn't the amount of time. It's the lack of diversification. The smoothing out process only works if the portfolio is diversified enough.

Yes, these are two different asset classes. But they're asset classes that are highly correlated to one another--they're prone to zigging and zagging at exactly the same time (as opposed to one zigging when the other is zagging, which is what you want).

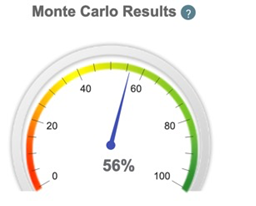

So when we look at the Monte Carlo results, which do take asset class correlation into account when projecting the probability of a plan succeeding:

Ouch!

Asking The Right Questions

This is a very extreme example of the perils of a lack of diversification. Things might look good or even great on a straight-line basis ($15 million!), but if you've got everything in highly correlated, very volatile asset classes, a (simulated as well as potentially real) bear market could hit your entire portfolio at the wrong time and wreak havoc. Looking at the Monte Carlo projections is critical to determining whether this is a big risk.

Which brings us back to the number-of-funds question. You can probably guess what our point is going to be here: What's important isn't the number of funds necessarily, but what they hold.

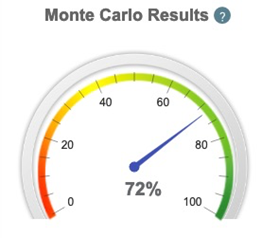

Once we move our couple into a well-diversified mix of asset classes (5% cash, 45% bonds, 20% growth stocks, 20% value stocks, and 10% international developed stocks), things look a lot better:

To be sure, the plan still needs some tweaking. We'd like to see that Monte Carlo result in the 85% range or higher. (They probably need to save more money.) But it's now on the right track anyway.

Eggs and Baskets

How you invest is important, but the number of funds you buy might not be. Just make sure you know what you own, and that you put your plan through its Monte Carlo paces like you can do in WealthTrace to make sure you're adequately diversified.

Do you know if you are diversified enough? If you aren’t sure, sign up for a free trial of WealthTrace to get started on your financial and retirement planning.